Lifestyle

Larry Schneider, my Fargo neighbor, invented the ‘minute shoe shine’

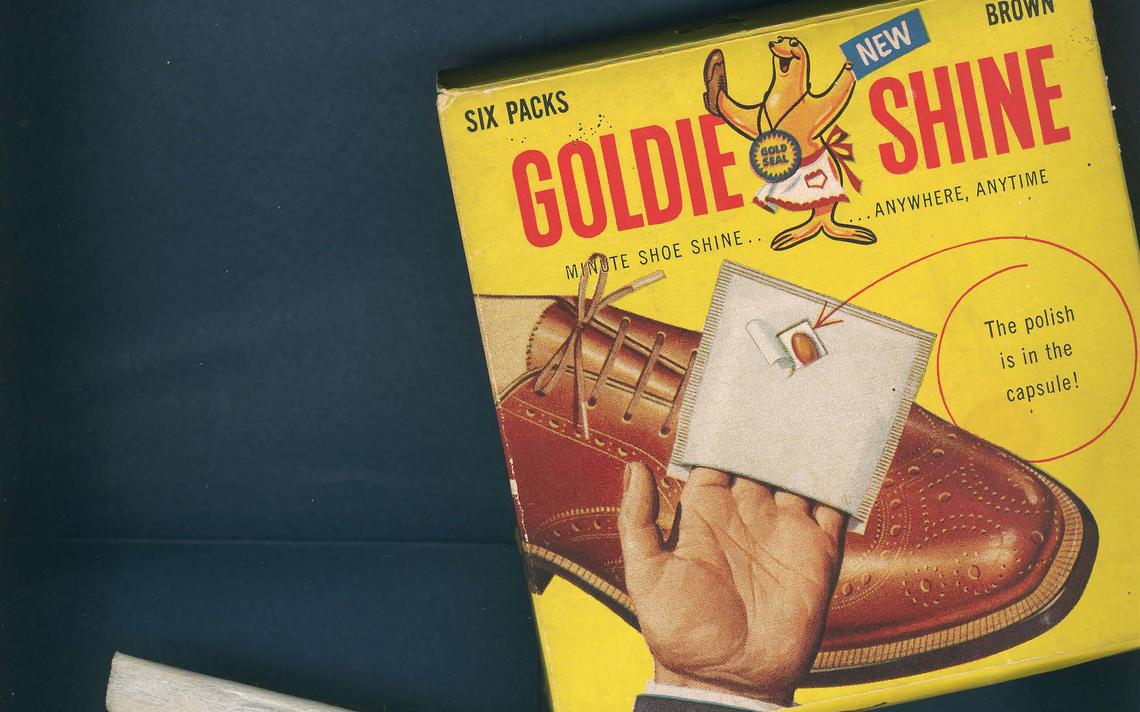

FARGO — Stored somewhere in my aging brain are three connected memories: In the early 1950s, Harold Schafer’s Bismarck-based Gold Seal Co. introduced a single-use shoe polishing mitt called Goldie Shine. It was invented by Larry Schneider. He was our neighbor on Third Street North in Fargo.

I remember using Goldie Shine. It was a multilayered paper mitt that held a pellet of polish. You inserted four fingers and used one ply to dust your shoes. You tore off that layer, pressed and broke open the capsule, and applied the polish. Then, you reversed your hand in the mitt and buffed your shoes to a shine. Clever!

Over the last few years, I asked some of my Fargo or North Dakota contemporaries if they remembered Goldie Shine. Few did. Not finding a history of Goldie Shine, I decided to write one, based on newspaper and other sources.

Internet sleuthing got me connected with Schneider’s daughter Sydney, who lives in an Atlanta suburb and is regarded by her siblings, Larry Jr. and Mary, as the family’s historian. We’ve talked and Sidney kindly shared with me her chapter on “The Goldie Shine Years: 1951–1956.”

Lawrence Albert Schneider was born in Kulm, N.D., in 1914. He graduated from Bismarck High School and cum laude from Concordia College in Moorhead. He was a standout athlete at both schools; in 1974, he was inducted into North Dakota’s Softball Hall of Fame.

He taught math and coached in Watertown, S.D., for a couple years, then worked for Standard Oil in Minot, N.D. In 1940, he married his college girlfriend, Melinor Myrha, of Fargo. He served as an ensign on a destroyer in the Atlantic in World War II. After the war, he was chief of special services for the Veterans Administration (now Veterans Affairs) in Fargo, helping disabled vets get jobs.

Many inventions are intended to solve a problem, whether great (like an anti-virus vaccine!) or small. For Schneider, the problem was personal. As a smart, enterprising kid growing up in Bismarck during the Great Depression, he shined shoes at a downtown corner. It was good money but resulted in stained hands. Sydney says her dad made additional money by challenging his customers to wager a quarter that he couldn’t name all of the then-48 states and their capitals, which he could do with ease.

By the late 1940s and still working at the Fargo VA, Schneider had refined his idea, and it was time to develop a prototype. A table in the Schneiders’ house was a laboratory, and Melinor Schneider was Larry’s co-experimenter. She sewed the early versions, then switched to heat-fusing, which a manufacturer would use.

Sydney remembers watching her mom using an iron to fuse the edges of five layers of material, trying to avoid “melting the plastic or clogging the iron with a gooey mess.” The outer layers would be Viskon, a trademarked cellulose fabric.

Viskon, Sydney tells me, was developed by Erwin O. Freund in 1925 to replace gut sausage casings, resulting in the first skinless sausages; and as a nonwoven fabric, it’s in a class of materials that still today are used for some face masks and other filters.

In 1951, Schneider brought his prototype to Harold Schafer. Schneider needed capital and marketing for his invention. Gold Seal, which had introduced Glass Wax in 1945 — and later would launch Snowy Bleach and Mr. Bubble — was losing money and needed someone who could help turn things around. The two agreed that Schneider would lead the company’s new Goldie Shine Division, in addition to marketing Gold Seal’s other products.

Creating a prototype on a household table was one thing; rapidly producing thousands on newly designed machines was another. It took months to settle on the exact specifications for the Viskon and polyethylene film. One snag: in experiments, the polish got too dry during what would be the time from manufacture to consumer use. Schneider got help from Dr. Carl Langkammer, his chemistry professor at Concordia, who now was a DuPont researcher in New Jersey.

With a few taps on my iPad, I found patent 2,790,982, applied for on Oct. 20, 1952, and granted May 7, 1957. The inventor is Lawrence A. Schneider of Fargo. The invention is blandly described as a “Single Use Applicator Package.” The six-page application has two pages of technical drawings. The remaining pages, in tiny print, describe the purposes of the invention and how it would work. A second patent application, filed later the same year and granted in 1958, covered the capsule.

In a March 1953 story, The Fargo Forum reported that a new “minute shoe shine,” the “brainchild” of a Fargo resident, was now “rolling off the production line in Chicago.” Goldie Shine would be available in packs of six, retail for 5 or 6 cents for each mitt and come in brown, black or neutral. Ads for Goldie Shine appeared in newspapers in markets across the nation.

Goldie Shines may have been rolling off the line, but they didn’t fly off retail shelves. Ten years later, in a profile of the hometown company, the Bismarck Tribune would report that Goldie Shine, Wood Cream and a charcoal lighter called Siz were among Gold Seal products that flopped. Goldie Shine, it said, “was tested nationally and failed.”

Based on early Goldie Shine sales, Schneider argued for shifting marketing dollars to target businesses in the hospitality and service sectors that would use it as an amenity for customers. Top Gold Seal executives initially resisted, then agreed. The shift helped, but not enough to save Goldie Shine as a Gold Seal product.

But Schneider wasn’t ready to throw in the towel. In September 1955, the Bismarck Tribune reported that Gold Seal’s Goldie Shine division had been purchased by a new company, Handee Pack Inc., capitalized at $100,000. Directors were Schneider, Melinor and his father-in-law, Melvin H. Myhra, president of Myhra Equipment Co. in Fargo.

Now Schneider was CEO, chief marketer, and financial manager for Handee Pack and its sole product, rebranded as Handee Shine. He traveled extensively in the United States and Canada to retain and grow sales. Hotels and dry cleaners were the best customers.

Handee Shines were shipped to Fargo from the manufacturer. A Fargo firm printed “Compliments of…” and company logos on the mitts. For a time, the Schneiders’ house served as a shipping center. Larry Jr. and Sydney, under their mother’s supervision, packed the mitts into boxes, taped and applied labels. Their dad paid them generously, Sydney says, but expected work that was neat and professional.

Schneider flew to Washington, D.C., seeking a loan for his new company from the Small Business Administration. No luck there, but he also visited Gabriel Hauge, a Hawley, Minn., native who had been a student at Concordia with Larry and now was a chief economic adviser to President Dwight D. Eisenhower. Despite the challenge of his new family business, Schneider was exhausted after five years of fast-paced work for Gold Seal and his invention. He’d developed a stomach ulcer. His doctor advised him to take a break or switch jobs.

Hauge sent Larry to a Commerce Department official who offered him a business-analyst position. Schneider accepted, and late in 1956, the family moved to Arlington, Va. A year later, North Dakota Gov. John Davis appointed Schneider as the first director of the state’s new Economic Development Commission. In the 1960s, Schneider served as director of Missouri’s Division of Commerce and Industrial Development for a couple years, then as executive vice president of that state’s Chamber of Commerce.

Next he returned to the Washington, D.C., area and held Commerce Department positions promoting industrial, agricultural and community development in several regions, including Appalachia, the Ozarks and Alaska, then served in the Interior Department as economic-development director in the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

Sydney says her dad long continued to believe in the potential for his invention and possible uses of the crushable-capsule technology, even as his passion and priorities shifted to economic development. She says an agreement awarded an Illinois company exclusive rights to sell Handee Shines, but it failed to deliver. Majority ownership of Handee Pack was sold to two outside individuals, and the company stumbled along until its demise in the mid-1960s.

Lawrence Schneider died March 6, 2010, in Springfield, Va., at age 95. Melinor Myrha Schneider died June 22, 2013, in Springfield, at 96.

Schneider’s obituary says he was “the creative genius of the Christmas stencils for use with Glass Wax.” Sydney Schneider’s history says her dad was watching a VFW–American Legion parade in Helena, Mont., in 1952 and seeing cars painted with sponsors’ names gave him an idea he shared with Gold Seal leaders: use Glass Wax to decorate seasonal store windows.

Three years later, about the time Schneider left the company, Gold Seal introduced in test markets its season-themed Glass Wax stencils, which for several years significantly boosted Glass Wax sales. A 1957 Advertising Age story on the company’s stencils “Gold Mine” said nobody at Gold Seal or its Minneapolis ad agency “can remember who should get credit for the stencil idea” and that Schafer “is still trying to find the hero to give him a special thanks.”

If you’re curious: Schafer sold Gold Seal to Airwick Industries in 1986. Glass Wax waned but was produced by multinational Reckitt Benckiser until 2002. The same company ended production of Snowy Bleach in 2007. The Gold Seal survivor is Mr. Bubble, “America’s favorite bath-time buddy,” now owned by The Village Co., Eden Prairie, Minn.

Little remembered today, Goldie Shine/Handee Shine was easy to use, left shoes with a nice shine and solved the stained-hands problem. But it was never a big success.

When I see Larry Schneider’s picture, he looks so familiar, although I was a kid and never really knew him. Still, I’m pretty certain that his years of experience at Gold Seal and in facing the challenges of launching his invention gave him lessons to share as he led state and national economic-development efforts, most targeted at helping some of the poorest areas of the nation.

Donn McLellan is retired and lives in Apple Valley, Minn., a Minneapolis–St. Paul suburb. He worked as a writer, editor and in public relations. During college, he was a writer, editor and reporter for WDAY Radio and TV over summers and holiday breaks, 1959–61.